We humans evolved as ground-based hunter-gatherers. When threatened, adrenaline is released, our heart rate increases and our bodies go into fight or flight mode – a strategy which worked really well for us until recently. Now, as pilots, strapped into the seat and unable to move, this response is very unhelpful.

The air is an unforgiving environment. Unlike driving on the road, we can’t pull over and take a break! Therefore it is critical that we are still able to operate effectively despite our bodies’ natural responses. This post will discuss how we can do this, focusing only on the stresses encountered in flight, not those which started previously on the ground.

Not Enough Stress?

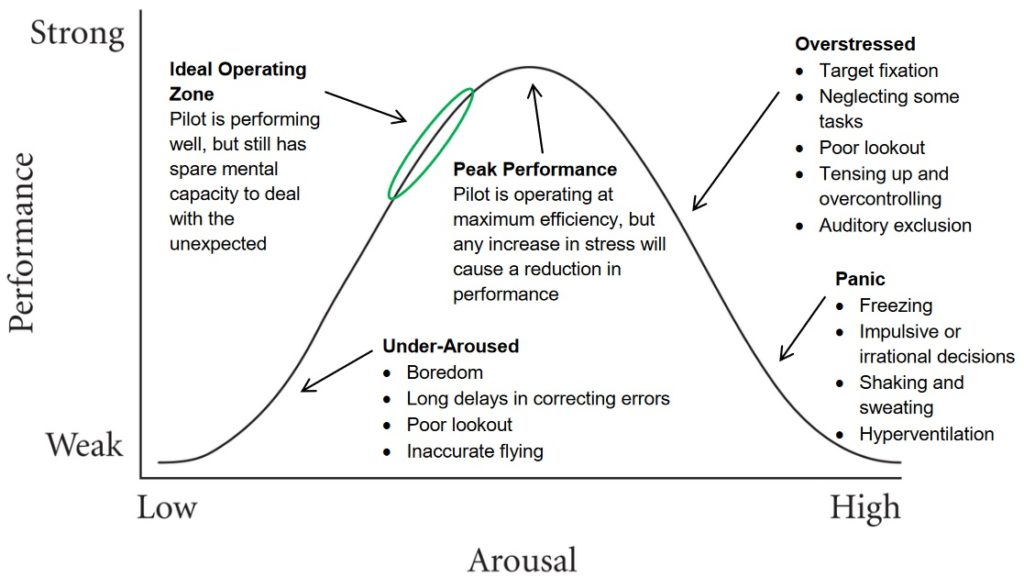

The Yerkes-Dodson law asserts a relationship between arousal, i.e. stress, and performance. It is most often portrayed in graphical form.

It should be no surprise that very high stress leads to poor pilot performance, but it’s interesting to see that an understimulated pilot also performs badly. In simple terms, we need some excitement or else we switch off. This means there might be times when we actually want to increase our stress levels in order to operate well – and it is common for pilots to do this by setting themselves goals. For example, if you are local soaring on an easy thermal day, set yourself a short task which keeps you within gliding range, and attempt to fly it as quickly and efficiently as possible. Then do it again, and try to beat your previous time. If you are soaring your local ridge, airbrake down a little and then climb back to the top of the lift zone as quickly as you can. When landing back at your home airfield, set yourself imaginary boundaries to simulate a spot landing in a farmer’s field. For the more experienced, if you’re suitably trained and rated, practise your aerobatics or competition finish manoeuvres. Doing these things will not only maintain your currency and sharpen your skills, but will also move you into the ideal operating zone for pilot performance.

In The Zone

Between under-arousal and overload there is an optimum stress level which allows a pilot to perform at his or her absolute best. While this sounds good, we should not aim to operate at such a high level all the time. This is because the air is unforgiving, and we must always have some spare mental capacity available to deal with the unexpected. The ideal operating zone for normal flying is circled green in the diagram below. This is where successful competition pilots are most of the time. When we are feeling good about our flying, we are in this zone.

Too Much Stress

Sometimes we make mistakes, bad decisions, or are confronted with events beyond our control, and we become overstressed. The situations which bring this on are different from pilot to pilot and depend on your experience, temperament and aptitude. Inexperienced pilots can be brought to this threshold by meeting a couple of other aircraft in the circuit or by a moderate crosswind, whereas experienced competition pilots can handle a huge workload before they are pushed over the edge. In either case pilots are most likely to become overstressed when trying something new, or flying in an unfamiliar area. Our personal stress tolerance also varies with our general health and wellbeing. One thing is for sure though – every pilot can become overstressed. So how can we tell if it is happening to us?

The symptoms of overstressing vary between individuals and you probably already have some idea of what yours are. Pilots in this condition will start ‘load-shedding’ – neglecting some parts of their usual work cycle, e.g. lookout. They may become transfixed by the cause of the stress and focus only on their chosen course of action without considering alternatives – this is known as target fixation, or sometimes the ‘red mist’. Auditory exclusion is also common – pilots will fail to notice warning alarms, radio calls, or the comments of the other crew member or passenger.

There are many examples of these symptoms in accident reports. Some pilots, who have selected the flap lever on approach instead of the airbrake lever, have flown the entire length of the runway without realising, then turned around and tried again! This is classic target fixation. Others have landed wheels-up despite the undercarriage warning alarm having sounded during the entire approach. These accidents should never be dismissed as stupid or (my favourite one) ‘pilot error’ – they contain lessons in human factors which apply to us all.

Calming Down

Due to target fixation, many of these symptoms are difficult for the pilot to notice at the time. The most obvious cues to the pilot are the physiological ones – tensing-up on the controls (pushing both rudder pedals at once), heart rate, feelings of anxiety, overheating/sweating, a dry mouth and, in severe cases, hyperventilation. As soon as you notice these signs, you need to find a way to reduce your stress and calm down.

De-stressing isn’t easy when you’re travelling at over a mile a minute, and probably in a downward trajectory. Here are the techniques which work for me:

- Fly the aircraft! Get the basics right – fly at a safe speed and attitude.

- Start moving in the right direction, away from the source of stress or towards a more manageable situation. In a glider this usually means moving towards your nearest suitable landing area. In heavy sink on a wave day, it means flying downwind. If you’ve been flying on a turbulent ridge, move away from it. If the weather ahead is deteriorating, turn around.

- List your options in your head. I prefer to start with my last resort, worst-case scenario. Knowing that even that would be survivable calms me down.

- At the same time as doing the above, reduce your physiological symptoms. Relax your muscles, take your feet off the pedals for a moment, breathe slowly and deeply, look around you and take a drink of water.

After a few minutes you will probably find yourself flying normally again, maybe even wondering what all the fuss was about.

Conclusion

We are all human and we are all subject to the limitations this brings. Developing an awareness of our personal stress levels is essential if we are to reach our full potential as pilots.

This article is good for thinking about thinking.

I find that I have to consciously relax my legs in my Discus, otherwise I’ll sit there semi-tensed. 350 hours over a long time and I’m still working on improving.

Very Useful Human Factor matter. This apply for any kind of situation in the life, as for any kind of pilot, glider or not.

Howdy!

Great post. Here are several more things to think about.

The first is that the capacity to deal with stress can be trained. An experienced pilot’s Yerkes Dodson curve would be considerably flatter at the top than an inexperienced pilot. This comes from desensitization to highly stressful situations.

The second is that the curve shifts depending on the difficulty of the task. If you train a certain task more, then it will be “easy” for you, and the curve will be flatter at the top and right. This is why it is critical for example to get your landings down to perfection… then you can still do the right thing even if the conditions become very violent and you’re under a lot of stress.

That said, “hard” tasks push the curve to the left… your performance will drop off sooner. Hard tasks include gathering information and making big decisions (situational awareness, judgment, and decision making).

The remedy is to recognize situations are usually the result of a continuous process. As an instructor once told me… “You were somewhere else before you got *here*!” And if you want to set yourself up for success, you have to pre-plan your choices before the heat cranks up as your capacity for wading through a range of alternatives will be compromised.

But with training, your capacity for execution will be OK even if you’re under a lot of stress.

All the best,

Daniel Sazhin

Soaring Economist